Political Competence

Leading change through other people can be a long and complicated process. For your benefit, I’ve tried to take one model for leading change and make it short, at least. This is a pretty dense summary of how to practice political competence. This phrase may turn some people off, but it is the correct word for getting to know how to influence other people by meeting them where they are rather than asking them to meet you where they are. Bite a piece of this essay off for a closer examination of your own process for leading change through others.

A key leadership competency is the ability to take ideas and translate them into action. To do this, a leader needs political competence. Knowing how to bring others along with you (especially when you do not have authority) is how real change gets made. Outlined below are steps* you might consider in your strategy to lead your next idea from thought to reality.

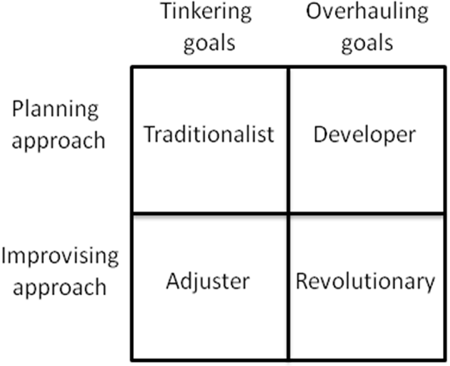

Know your approach. Are you a planner or an improviser? When you consider a change, do you think each step that need to take place before reaching your goal; consider the past as a direct indicator of future performance; that the answer can be found in the data? Or, assuming that the future is unpredictable, do you wait to see what will happen with this decision before you move on to make the next decision?

Know your strategy. Is your method to work around the edges of the defined problem by making small but necessary changes, or is your method a major shift in the way of thinking for your group? Depending upon the problem to be solved (and the individual) solutions can have “tinkering goals” or solutions can have “overhauling goals”.

Know your style. Combining approach and strategy, there are four leadership styles. (See Figure) The resistance brought about by change is not whether or not a change should happen, but the resistance is actually to the approach to the change and the scale of the change.

Know your stakeholders. Take serious time to list everyone who has an interest in, an opinion about or influence over the change that you want to make. Think upward, think downward and think of your colleagues in other departments. Think outside the organization.

Know your stakeholders’ style. Considering their past initiatives, do your stakeholders tend to be planners or improvisers; tinkerers or overhaulers? Stakeholders with the same style as you tend to be allies in change. Those in an opposite quadrant are the most likely resistors. Those who share goals, but have different approaches are more likely allies, and those who share approaches but have different goals are more likely to be resistors.

Build a coalition. Start with those who share your style, but be careful to not be accused of creating a cult or fall into ‘group thinking’. Then find interest groups who share your goals, but don’t get accused of grandstanding. Find leaders with similar approaches, but don’t get accused of conspiracy. Use a balance of all three strategies to diversify your base and reduce the resistance.

Justify your actions. There are several possible methods to engage potential allies. “Rational” (logical) methods are those that rely on upon numbers–usually $ or data to make a case. The “mimicking” strategy takes the fewest resources to promote and to understand. The motivation is that “everyone is doing it”. “Regulation” strategy blames others who are the forcing change. While it might be true, this strategy has limits. Similar, , the “expectations” strategy considers the stakeholder norms and standards and the need to comply.

Gather buy-in. Engaging potential resistors requires greater persuasive techniques. Informal persuasion allows you to probe individuals to determine what motivations may move them to your side before introducing your own. Formal negotiations require you to openly request their support. A platform of one or few motivations results in a narrow coalition. Broader coalitions are built on multiple motivations and on strategy, but run greater risk of rejection.

Lead Now you have followers–you are the leader. A leader must continue to solidify the coalition, working out differences between themselves and team members and between team members, while continuing to increase the coalition. This happens until a tipping point is reached in which your idea becomes the “new norm”.

Political competence begins with an awareness of the processes by which you influence others to adopt your ideas. Political competence does not require a position title. The most important component of political competence is credibility which, among other needs, requires personal integrity.

*Steps adapted from Get Them on Your Side, Dr. Samuel Bacharach, Platinum Press, 2005

A 3-step process to help you and your employees create lasting behavioral change.